Address

39 Fen End Lane.

Spalding, Lincs. PE12 6AD.

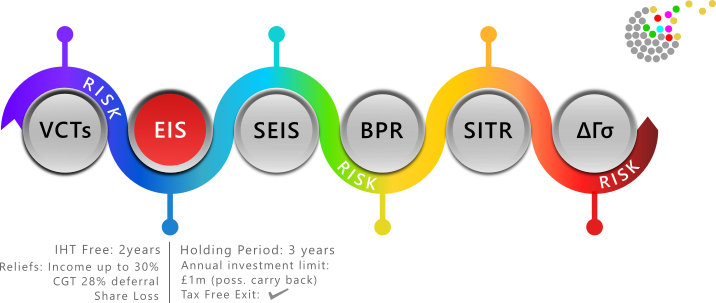

EIS – Enterprise Investment Scheme

The Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) was established in 1994 as a way of encouraging private investment in small and medium sized companies that are typically higher risk and find it harder to raise finance.

Investors benefit from a range of generous tax reliefs that can be claimed back via their self-assessment tax return when the company they have invested in provides them with evidence that they are compliant with the conditions of the scheme.

This process of compliance involves the company successfully making what’s known as an Advanced Assurance Request (AAR) to a division of HMRC known as the Small Company Enterprise Centre (SCEC). HMRC use data from the SCEC and individual self-assessment returns to produce a semi-annual report to give us an idea of the amount of participation in this financing initiative.

In the April 2017 report, it states that since 1993/94 over 26,000 companies have received investment through the scheme and over £15.9 billion of funds have been raised. And in the last financial year of complete data, 2015/2016, 3,285 companies raised a total of £1,647 million and of the total number of AAR applications received 85% were successful – matching the average since 2006/7.

So, that tells you this is an established part of the investment landscape, albeit with its own set of conditions, benefits and risks.

Investment in those 3,285 companies in 2015/16 are mostly made into a single compliant company or an EIS fund. The fund doesn’t operate in the manner of a legal pooled investment entity like a venture capital trust, but operates a collection of investments under the terms of a discretionary management contract. And it is these EIS funds that are offered to the general investing public where suitable.

There is also a self-select third option where a manager sources a pool of approved investments and investors can allocate their investment according to their risk profile and industrial sector preferences.

However, it is worth noting that probably over half of all the EIS activity in the year is attributable to single company EISs where an established individual business angel is the sole investor. The individual limit for claiming any of the relief on an EIS investment is £1mln.

Investors, who must be aged 18 or over, can invest up to £1 million in an approved scheme and subsequently are able to receive the following tax benefits:

- Capital gains deferral up to 28%

- Income tax relief 30%

- IHT free after 2 years

- Loss relief

- Tax free capital growth

These reliefs only apply if both the investment is maintained for a minimum of three years and the investee company remains compliant during that period.

The companies themselves must be unquoted i.e. not listed on a recognised stock exchange. It may subsequently become listed without investors losing their respective reliefs as long as this wasn’t already organised when the shares were first issued, which might imply limited risk.

Investments may trade on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) or PLUS Markets as neither are currently recognised within EIS rules as exchanges.

Compliant companies are also limited to certain sectors which may change over time, although not, as yet retrospectively. One example of this was the removal of energy companies where revenue was derived from feed-in-tariffs from solar panel investments. These have proved to be reliable for investors with exit values typically above £1.15 for every £1 invested, but HMRC recognised that returns were more akin to an asset backed corporate bond than an equity investment in a high innovation start up.

There is a long list of applicable risks in addition to this risk of changes to the rules. These are by definition unlisted new ventures, and some have assets that may themselves be volatile and illiquid.

Therefore, one of the main risks is that of exiting the investment and that is also a major consideration for due diligence.

Ideally, a subsequent round of fund raising at a premium to the investor’s original provides a simple profitable sale and, if it comes from a connected party, it is deemed to be fair.

Where there are established assets it may be possible to create a charge to pay those investors wishing to sell. And if the business is particularly cash generative it may be possible to arrange a share buy-back, but there are strict corporate governance rules for this approach. If none of the above are possible then the investor will be left holding the shares.

Please refer to our more complete list of key risks here. The HMRC has a series of pages and links to this topic which can be found here.